Édith Ouy

Outline

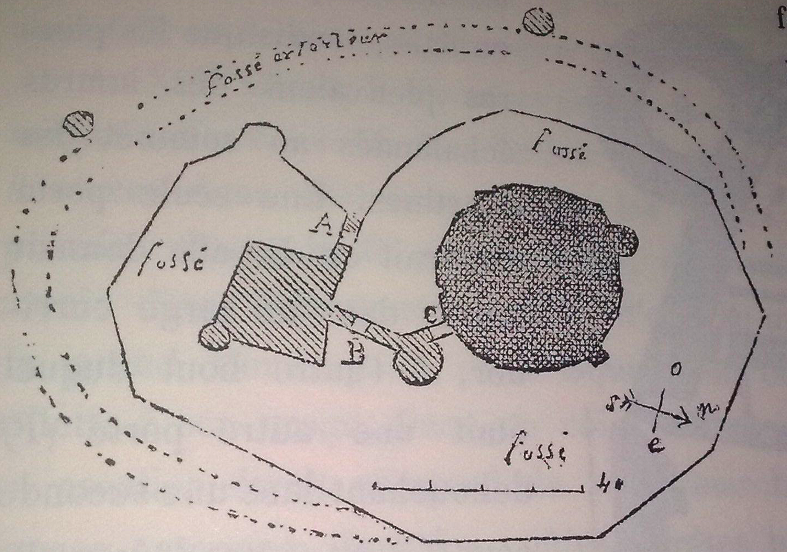

The Château de La Brède from the 11th to the 16th centuryMap of the fortifications of the Château de La Brède. Drawing by Léo Drouyn (La Guienne militaire, 1865).

View of the access bridges to the Château de La Brède.

View of the aula of the Château de La Brède.

The Château de La Brède in the 17th and 18th centuries

View of Montesquieu’s room on the ground floor of the Château de La Brède.

Historical map of the domain of La Brède in the eighteenth century (Bordeaux, Bibliothèque municipale, LAB 4855).

The hedge-row in the park of La Brède.

View of the Château de La Brède from the Tapis Vert or ‘green carpet’.

The Château de La Brède after Montesquieu: between family life and cultural site

The Château de La Brède from the 11th to the 16th century

“It will be my pleasure to take you to my country house at La Brède, where you will in truth find a gothic château […]”

1Assigning a date to the Château de la Brède is a difficult matter. The first mentions of a lord of La Brède are mixed into a fable relating the duel in 1079 between a lord of La Lande (or Lalande), lord of La Brède, and the champion of the army of Navarre, Hernandes. The victory of the lord of La Lande put an end to the siege of the city of Bordeaux. There must have been then at La Brède a fortress of the plains château variety, built on an artificial rise supplied by the earth coming from the digging of the trenches. The construction was probably of wood, as were most aristocratic structures of the Romanesque period.

2After Guillaume de La Lande, lord of La Brède, was found guilty of murder in Bordeaux in 1283, the seneschal’s lieutenant ordered the château to be seized. It was attacked by the provost of L’Isle and quite probably destroyed. Its reconstruction after this sacking dates from 1285, date of the first document mentioning the Château de La Brède (Bémont, p. 239 and 286). In 1306, a reconstruction was authorized by the king of England, overlord of the La Brède property. According to Léo Drouyn, “from the very form of its overall plan, we can certify that the Château de La Brède is one of the oldest fortresses in the Gironde” (La Guienne militaire, p. 348), but there is a lack of documents for any more precision. The château’s structure evolved as the trenches (in other words, the moats) were extended. The first enclosure on the Romanesque rise remained and a large, square court was surrounded by ditches, which then became the château’s draining channel. These two elements were merged to allow the circulation of water.

3La Brède was not entirely spared by the conflicts and consequences of the Hundred Years’ War. In 1419 the château was damaged by French artillery shells and Jean de La Lande obtained formal authorization by letters-patent to refortify his château. A third, elliptical moat was then created and merged with the two previous ones. In 1453, Jean de Lalande (1409-1491, his son) left for England. His properties were confiscated by the king of France and the Château de la Brède was given to Louis de Beaumont, knight and seneschal of Poitou, who did not live there. In 1463, it was restored to Jean de Lalande.

4The château was then surrounded by a nearly circular moat forty meters in diameter.

A succession of drawbridges protected by walls with arrowslits (some of which overlook the guard tower at ground level) allowed monitored access to the château’s main courtyard. It was entered through a door in the middle of the façade that opened onto a corridor leading to another court where the château’s well was located. The rear court was protected by a projecting tower about thirty meters high. To the corridor’s left was the great lower room which gave access to lodgings for the garrison (placed opposite the entrance to the fortress). On the right were the kitchen and commons. Above the lower great room was the upper great room or aula, in which there was a vast chimney decorated by men on horseback across the hood, as were probably all the walls of the great room. It was in preparation for restoration that behind the coats of arms of the present library (situated in the great medieval hall) were found the remains of paintings representing knights that could date back to the end of the 15th century (work begun in 2013). The rest of the upper level served as lodgings for the lord’s family.

5Following the marriage of Jean de La Lande’s great-granddaughter, the Château de La Brède became the property of the Penel (or Pesnel) family. In 1577, Jean de Penel had the walls surrounding the moats crowned with a parapet. These walls were in addition brought into a single ensemble, thus creating a large lake. The château was no longer a fortress but had become a vacation home. Only three drawbridges remained. The insertion of mullion windows must date from the same period. The inside of the château also was modified: new rooms were installed behind the lower great room and a new door allowed free access to them without going through the main hallway. The château was henceforth in its definitive form, and the exterior structure was to vary little.

The Château de La Brède in the 17th and 18th centuries

« […] the Château de La Brède, which I have so greatly embellished since you last saw it, is the handsomest country seat I know […]”

6Jacques de Secondat (1654-1713), Montesquieu’s father, in 1686 married Marie-Françoise de Pesnel (1665-1696), thus bringing the barony of La Brède into the Secondat family. He surely occasioned some of the interior changes in the château. To him indeed are attributed the installation of some of the “Capucine-style” wooden paneling (darkly painted paneling) in walnut and of fireplaces painted to match the transoms (floral motifs or landscapes) of the ground-floor rooms. It was probably also Jacques de Secondat who transformed the upstairs medieval great room into a library.

7It was in this château that Charles Louis de Secondat was born on 18 January 1689. He was to succeed his father as Baron de La Brède in 1713. His influence on the structure itself of the château appears minimal: he began no great modernization project, and the inventory of the contents after his death (Gironde departemental archives, 3 E46917) allows us to imagine a very dark interior, perhaps even a bit antiquated. The furniture is indeed described as “old”, “patched and broken”. It was mostly made of walnut. Nor do we find any traces of formal furnishings or precious works of art. Aside from the ground-floor salon, there was no large, formal reception room at La Brède once the medieval aula was transformed into a library. Nevertheless, Montesquieu marked the château with his presence, for at the end of his life he relinquished the lord’s room, traditionally upstairs, for an old guard’s lodging remade into a bedroom on the ground floor. It is this bedroom that was to remain after Montesquieu’s death the trace of his life at La Brède.

8We must nevertheless point out that only evidence from after Montesquieu’s death places his room on the ground floor: the closest chronological document, the inventory after his death, does not mention a room for his own particular use. In 1785, Sophie von La Roche travels throughout France and does not fail to come as far as the Château de La Brède, thus fulfilling “a wish more sacred [to me] than any of those [she] ever made” (p. 207). She describes the Château de La Brède and clearly specifies that, to reach Montesquieu’s room, she was led “by a spiral staircase, passing through a room tall as a church” (p. 210), which situates the room on the second level, beside the library. On the other hand, Francisco de Miranda, visiting the Château de La Brède in March 1789, speaks of an “apartment where Montesquieu regularly came to sit before the fire after dining”, situated on the ground level, but also upstairs “the room where he was born, in the room where he slept” (p. 366-367). Might there have been two rooms used at the same time by Montesquieu, only one of which was preserved from later changes? That would explain the sanctuarization of the ground-level room as the ultimate testimony to the presence of Montesquieu in the Château de La Brède.

9On the other hand, Montesquieu profoundly transformed the surroundings of the Château de La Brède. There were two reasons, at first practical ones, for these modifications, with large irrigation projects and sanitation of the neighborhood so as to permit cultivation of the land. It consisted principally of digging the trenches and gutters to drain the prairies around the château (letter of 30 September 1744 [OC, t. XIX, no. 571] from Montesquieu to abbé Guasco: “[…] we will plant woods and create prairies […]”). There were also esthetic reasons for reorganizing the park, with the desire to mark the domain with his presence. Taking his inspiration directly from Dezallier d’Argenville’s Theory and Practice of Gardening, in which lovely gardens are treated in depth, published in 1709 and bought by hum in 1722 (Catalogue, no. 1387 [‣]), Montesquieu created in his park a regular garden, with flower beds and a coppice. It was a double star-shaped design allowing for the walking avenues to crisscross at several points with a succession of small junctions. The yoke-elm is the principal ingredient, used especially to create palisades, in other words a wall of vegetation, thus becoming a “bower” (then it is “small yoke-elms about two feet high, and thick as a little finger at the base” that are used: Dezallier d’Argenville, p. 309).

10We can see the importance of these projects for Montesquieu throughout his correspondence with the Marshall de Berwick, and the interest shown by these exchanges in techniques of irrigation and organization. Thus, in a letter dates 10 January 1724, Berwick writes to Montesquieu: “I hope that this spring you will communicate all your plans to me, so I may draw from them ideas for Fitz-James, and also give you my advice” ( Correspondance I, letter 65, p. 81). Two years later, it is Montesquieu who writes to the marshall: “I am presently cutting through mature forest and Fitz-James is my sole model. Even the small avenues that are so pretty I am transplanting to my land” (27 July 1726, ibid., lettre 213, p. 243).

11This aspect of the park has been restored to the Château de La Brède (2010-2014). Different plans for the park having been discovered and analyzed by Françoise Phiquepal, a landscape architect, it was possible to relocate the design for the coppice and bower. A grand “green carpet” has thus been restored with its ditches, making it possible to rediscover the play of perspectives which Montesquieu was seeking.

12After his stay in England (he returned in 1731), Montesquieu decided to create a new garden at La Brède. He wrote to Guasco in August 1744 to tell him about his château and its “charming surroundings, the idea for which [he] got in England”. It is “a succession of landscapes […] that open onto the countryside and attract the eye as a prolongation of the garden” (Michel Conan, p. 21). Regularity was over: time to let Nature be (or appear to be) Nature in its original state, without human intervention.

13The form it takes at La Brède is a partition of the domain, since the regular garden remains and the English garden is created in another part of the park, situated in the southeast, opposite Montesquieu’s second bedroom. Here appears Montesquieu as “gentleman farmer”, walking in his woods and prairies, following closely the reorganization of his park and taking an interest in everything taking place there. It is one of the images that will remain of Montesquieu, often represented in 19th-century engravings wearing a shirt, walking through his park or talking with persons working for him. Montesquieu thus anticipates the Anglophilia that would be stylish in the second half of the 18th century. In a work of 1842 we see two English visitors at La Brède who are pointing out the resemblance between the park of the château and their native land (Tastu, 1846).

The Château de La Brède after Montesquieu: between family life and cultural site

“Assidue veniebat” (inscripting on the front of the Château de La Brède.)

14At the outbreak of the French Revolution, the Secondat family was no longer living at the Château de La Brède. Montesquieu’s son, Jean-Baptiste de Secondat, lived mainly in his Bordeaux home on the rue Sainte-Eulalie. It is he who is Baron de La Brède. Montesquieu’s land (in Lot-et-Garonne) was inherited by his younger sister Denise at their father’s death. He was arrested and imprisoned on 3 January 1794 because, his son having emigrated, he was suspected of anti-Republican complicity. He was freed after 27 days’ captivity and died soon afterward, on 17 June 1795.

15Charles Louis de Secondat (1749-1824), Montesquieu’s grandson and Baron de La Brède, who had distinguished himself during the American war of Independence, left France in 1792 and, after a time in Spain, joined Condé’s army quartered in Germany. After the defeat of the royalist armies in Quiberon in 1795, he was to emigrate to England, or at least letters dated 1796 allow this to be surmised. In this way the château entered into the property confiscated as national assets and as such put up for sale. That did not happen, but the château’s inoccupancy during this time left traces and the early years of the 19th century were devoted to making repairs.

16With Charles Louis de Secondat considered as an emigré and living in England (he returned only once to La Brède, rather briefly in 1818), the task of overseeing these operations fell to his cousin Joseph Cyrille de Secondat (1748-1826), son of Denise de Secondat and Baron de Montesquieu. The correspondence between the two cousins, preserved at the municipal library of Bordeaux (Ms 2739) exposes them at length, with frequent reminders of the financial imperatives. The frame draws first attention as the most urgent item. Next come outside repairs and the tiles of the upstairs great room (the library). Only then are interior repairs addressed with modifications of the inner walls, the ceilings, and windows. Nevertheless, Charles Louis requests that there be “no changes […] in this old habitation of [his] grandfather. His memory must be respected in the place which gave him birth”. The will to preserve Montesquieu’s memory was not the only reason motivating this oft-repeated request: there was also a very considerable financial aspect. This will to fix the legacy of Montesquieu in the château’s organization was respected, and the downstairs bedroom where the author spent his last years would not longer be subject to 19th-century projects and modifications.

17At the death of Charles Louis de Secondat (1824), it was the son of his cousin Joseph, Prosper de Secondat (1797-1871) who inherited the property and title of Baron de Montesquieu et de La Brède. The Château de La Brède became the family place of residence and many changes were made. The exterior form was not modified because of the presence of the moats, but its appearance, distribution, and inner arrangements testify both to the evolution of taste in the direction of the neo-gothic or “troubadour” which was more and more in vogue, and of the style of living within a château. The nobility was going middle-class, which had repercussions on the interior spaces.

18We can point to three grand phases in the construction. The first was the work of the architect Henri Duphot who brought about the crenellation of the principal façade and the window arches of the dining room, also a creation of the 19th century. Then came the project of Gustave Allaux in the years 1863-1864. The east façade was again restyled, with the probable addition of windows in the upper part. At the same time the intention was to modify the great stairway, which would finally be entirely rebuilt by Dubert.

19But it was especially the projects directed by Paul Abadie (1812-1884), a pupil of Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc, assisted by Jean Valleton (1841-1916), who modified the organization of the château. This was between 1870 and 1877. The distinction between historical and lived-in rooms became clearer. The active rooms were considerably modified and their distribution modernized by a system of corridors that did not exist until then. The desire for convenience also reached (to) the parts reserved for servants and a part of the attic was converted into rooms for the maids. These changes had been made when Charles de Secondat (1833-1900, son of the former) became Baron de La Brède.

20The modernization of the Château de La Brède did not change the desire to keep intact the trace of Montesquieu’s presence. Visitors would ask to contemplate the room where Montesquieu had spent the end of his life, at first local learned societies or academies: thus the archeological society of Tarn-et-Garonne was received at the château de La Brède on 23 October 1890 and left a very detailed description of its visit (Bordeaux, municipal library, Ms 2750). The desire to visit the château nevertheless dates back farther: the visit of Sophie von La Roche, the first to leave a testimony to her visit, has already been mentioned. Others can be added: La Brède became an obligatory passage for any author travelling in the Gironde. Stendhal, for example, left us a fairly precise description of what he could see at the château de la Brède when he came in 1838 (moreover, he situates Montesquieu’s bedroom on the ground floor: p. 99-100).

21There are few documents to inform us about the history of the château in the 20th century. After the construction directed by Paul Abadie, it appears that there were no further modifications to the château either in its exterior structure nor in its interior organization. The two World Wars had no major impact on the domain, despite the fact that German troops occupied it during World War II. The château also served during this period for the preservation of art works and objects from the east of France.

22Just as the beginnings of the Château de la Brède’s history are conflated with fable, a modern mythology representing Montesquieu on his lands slowly takes the place of historical information. The château ceased to be a family residence in 2004 upon the death of the countess Jacqueline de Chabannes to become a cultural and tourist site, each person searching the trace of trace of Montesquieu at La Brède.

Bibliography

Montesquieu, Correspondance I (1700-1731), OC, t. XVIII, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1998; Correspondance II (1731-1747), OC, t. XIX, Lyon/Paris: ENS Éditions/Classiques Garnier, 2014.

Antoine Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, La Théorie et la pratique du jardinage où l’on traite à fond des beaux jardins (1st edition 1709), Arles: ENSP, Actes Sud, 2003.

Sophie Von La Roche, Journal d’un voyage à travers la France 1785, 1st edition 1787, translation by Michel Lung (ed.), Bordeaux: Éditions de l’Entre-deux-Mers, 2012.

Francisco De Miranda, Colombeia. Segunda seccion, el viajero ilustrado 1788-1790, t. VIII, Caracasa: Ediciones de la Presidencia de la Republica, 1988 (trans. Françoise Provost in progress).

Charles Grouet, Notice sur le château de La Brède, Bordeaux: Ramadié, 1839.

Amable Tastu, Alpes et Pyrénées: arabesques littéraires composées de nouvelles historiques, anecdotes, description, chronique et récits divers, Tours: A. Mame, 1846.

Henri Ribadieu, Les Châteaux de la Gironde, Bordeaux: J. Dupuy, 1856.

Léo Drouyn, La Guienne militaire, Bordeaux-Paris: Didron, 1865.

Edouard Guillon, Les Châteaux historiques et vinicoles de la Gironde avec la description des communes, la nature de leurs vins et la désignation des principaux crus, tome 4, Bordeaux: Coderc, Degreteau and Poujol, 1869.

Charles Bémont, Rôles gascons, t. II (1173-1290), Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1900.

Stendhal, Voyage dans le Midi de la France, Paris: Gallimard, 1992.

Louis Desgraves, Le Château de La Brède, Bordeaux: Bière, 1970.

Jacques Gardelles, Les Châteaux du Moyen Âge dans la France du Sud-Ouest: la Gascogne anglaise de 1216 à 1327, Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1972.

Jacques Gardelles, Châteaux de la Gironde, Paris: Nouvelles éditions latines, 1981.

Jacques Gardelles, Le Guide des châteaux de France. Gironde, Hermé, 1981.

Louis Desgraves, Montesquieu, Paris: Mazarine, 1986.

Jean-Paul Avisseau and Claude Laroche, “Le château de La Brède et l’architecte Paul Abadie”, Revue archéologique de Bordeaux, 86, 1995, p. 105-128.

Michel Conan, Dictionnaire historique de l’art des jardins, Paris: Hazan, 1997.

Louis Desgraves, Inventaire des documents manuscrits des fonds Montesquieu de la bibliothèque municipale de Bordeaux, Geneva: Droz, 1998.

Philippe Durand, Le Château-fort, Bordeaux: Jean-Paul Gisserot, 1999.

Marie-Madeleine Martinet and Laurent Châtel, Jardin et paysage en Grande-Bretagne au XVIIIe siècle, Paris: CNED, Didier Érudition, 2001.

François Cadilhon, Jean-Baptiste de Secondat de Montesquieu: au nom du père, Talence: Presses universitaires de Bordeaux, 2008.

François Cadilhon, "La Brède", DM 2008 (2013), http://dictionnaire-montesquieu.ens-lyon.fr/fr/article/1376477019/en/

Catherine Volpilhac-Auger, Un auteur en quête d’éditeurs? Histoire éditoriale de l’œuvre de Montesquieu (1748-1964), Lyon: ENS Éditions, 2011.